News

Welcome to the World of Image-Bar!

We are delighted to announce the highly anticipated launch of Image-Bar, an online source of fine art and historical images. Whether you are a publisher, an individual or an organization wanting to enrich publications, presentations or websites, you are certain to find what you are looking for in our substantial archive of digital images, which ranges from revolutionary masterpieces of the past to unique, contemporary art.

The founding principle of Image-Bar was to provide excellent quality art from all eras in an accessible and convenient online format. The importance we place on ensuring the superb quality of art stems from our acute awareness that the Internet should enhance and lend something extra to original artwork, rather than take away the authenticity that makes art all that it is.

As we all move forward into an increasingly digital age, Image-Bar is dedicated to ensuring the permanence and accurate digital preservation of painted art, for its expression, influence and value remains essential. Although our collection grows by the day, we already have tens of thousands of images available online, available to be enjoyed at the click of a mouse. All of our image files are uploaded in JPEG format, which is supported by all mainstream software, for maximum user ease and compatibility.

We invite you to look around our art gallery and set up your free user account should you wish to make a purchase. If you have any questions about our service, you can contact us on info@image-bar.com. Follow us on Twitter or like our Facebook page to hear all about our latest offers and our brand new collections.

2012-03-14 05:45:17Ruskin – Modigliani: The Scandal of the Pubic Hair

Exhibition: Modigliani

Date: 23 November 2017 – 2 April 2018

Venue: Tate Museum, London.

Amedeo Modigliani was born in Italy in 1884 and died in Paris at the age of thirty-five. He was Jewish with a French mother and Italian father and so grew up with three cultures.

A passionate and charming man who had numerous lovers, his unique vision was nurtured by his appreciation of his Italian and classical artistic heritage, his understanding of French style and sensibility, in particular the rich artistic atmosphere of Paris at the turn of the 20th century, and his intellectual awareness inspired by Jewish tradition.

Unlike other avant-garde artists, Modigliani painted mainly portraits – typically unrealistically elongated with a melancholic air – and nudes, which exhibit a graceful beauty and strange eroticism.

In 1906, Modigliani moved to Paris, the centre of artistic innovation and the international art market. He frequented the cafés and galleries of Montmartre and Montparnasse, where many different groups of artists congregated.

He soon became friends with the Post-Impressionist painter (and alcoholic) Maurice Utrillo (1883-1955) and the German painter Ludwig Meidner (1844-1966), who described Modigliani as the “last, true bohemian” (Doris Krystof, Modigliani).

Modigliani’s mother sent him what money she could afford, but he was desperately poor and had to change lodgings frequently, sometimes abandoning his work when he had to run away without paying the rent.

Fernande Olivier, the first girlfriend that Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) had in Paris, describes one of Modigliani’s rooms in her book Picasso and His Friends (1933):

A stand on four feet in one corner of the room. A small and rusty stove on top of which was a yellow terracotta bowl that was used for washing in; close by lay a towel and a piece of soap on a white wooden table. In another corner, a small and dingy box-chest painted black was used as an uncomfortable sofa.

A straw-seated chair, easels, canvasses of all sizes, tubes of colour spilt on the floor, brushes, containers for turpentine, a bowl for nitric acid (used for etchings), and no curtains.

Private collection

Modigliani was a well-known figure at the Bateau-Lavoir, the celebrated building where many artists, including Picasso, had their studios. It was probably given its name by the bohemian writer and friend of both Modigliani and Picasso, Max Jacob (1876-1944).

While at the Bateau-Lavoir, Picasso painted Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), the radical depiction of a group of prostitutes that heralded the start of Cubism.

Other Bateau-Lavoir painters, such as Georges Braque (1882-1963), Jean Metzinger (1883-1956), Marie Laurencin (1885-1956), Louis Marcoussis (1878-1941), and the sculptors Juan Gris (1887-1927), Jacques Lipchitz (1891-1973) and Henri Laurens (1885-1954) were also at the forefront of Cubism.

The vivid colours and free style of Fauvism had just become popular and Modigliani knew the Bateau-Lavoir Fauves, including André Derain (1880-1954) and Maurice de Vlaminck (1876-1958), as well as the Expressionist sculptor Manolo (Manuel Martinez Hugué, 1872-1945), and Chaim Soutine (1893-1943), MoïseKisling (1891-1953), and Marc Chagall (1887-1985). Modigliani painted portraits of many of these artists.

Max Jacob and other writers were drawn to this community which already included the poet and art critic (and lover of Marie Laurencin) Guillaume Apollinaire (1880-1918), the Surrealist Alfred Jarry (1873-1907), the writer, philosopher, and photographer Jean Cocteau (1889-1963), with whom Modigliani had a mixed relationship, and André Salmon (1881-1969), who went on to write a dramatised novel based on Modigliani’s unconventional life.

The American writer and art collector Gertrude Stein (1874-1946) and her brother Leo were also regular visitors.

Modigliani was known as ‘Modi’ to his friends, no doubt a pun on peintremaudit (accursed painter).

He himself believed that the artist had different needs and desires, and should be judged differently from other, ordinary people – a theory he came upon by reading such authors as Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867), and Gabriele D’Annunzio (1863-1938).

Modigliani had countless lovers, drank copiously, and took drugs. From time to time, however, he also returned to Italy to visit his family and to rest and recuperate.

In childhood, Modigliani had suffered from pleurisy and typhoid, leaving him with damaged lungs. His precarious state of health was exacerbated by his lack of money and unsettled, self-indulgent lifestyle.

He died of tuberculosis; his young fiancée, Jeanne Hébuterne, pregnant with their second child, was unable to bear life without him and killed herself the following morning…

To get a better insight into the life and the work of Modigliani, continue this exciting adventure by clicking on:Modigliani , Amazon UK , Amazon US , Ebook Gallery , iTunes , Google , Amazon Australia , Amazon Canada , Amazon Germany , Ceebo (Media Control), Ciando , Tolino Media , Open Publishing , Barnes&Noble , Baker and Taylor , Amazon Italy , Amazon Japan , Amazon China , Amazon India , Amazon Mexico , Amazon Spain , Amabook , Odilo , 24symbols , Arnoia , Nubico , Overdrive , Amazon France , numilog , youboox , Cyberlibris , Kobo , Scribd , Douban , Dangdang

2017-12-15 02:21:21

Arcimboldo: The Great “ABBUFFATA”: An Italian Tradition From Arcimboldo to Marc Ferrari

Exhibition: La grande bouffe : peintures comiques dans l’Italie de la Renaissance

Date: October 28, 2017 – March, 11, 2018

Venue: The Musée Saint Léger in Soissons, France.

Arcimboldo

(1527 – 1593)

Son of the artist Biagio Arcimboldo and Chiara Parisi, Giuseppe Arcimboldo was born in Milan in 1527. Of noble descent, Arcimboldo‘s family originated from the south of Germany, with some family members relocating to Lombardy during the Middle Ages.

Numerous variations of the spelling of the family name can be found: Acimboldi, Arisnbodle, Arcsimbaldo, Arzimbaldo, or Arczimboldo; the ‘boldo’ or ‘baldo’ suffix is a mediaeval Germanic derivative. Likewise, Arcimboldo signed his first name in several different ways: Giuseppe, Josephus, Joseph, or Josepho are some of the examples that can be found.

In his work La noblità di Milano (1619), Paulo Morigi charted the history of Arcimboldo‘s family and confirmed his nobility, despite very uncertain sources, by tracing his roots back to the time of Charlemagne, when a nobleman named Sigfrid Arcimboldo served in the court of the Emperor. Out of sixteen Arcimboldo children, three were knighted and one amongst them settled in Lombardy. This is how the Italian branch of the family came to be founded. To support his claims, Morigi declared that his narrative came directly from Giuseppe Arcimboldo, a trustworthy gentleman with a respectable lifestyle.

Also in La noblità di Milano, Morigi continued to develop the history of the Arcimboldo family, although limiting this to the Italian branch residing in Milan. He stated that the widower Guido Antonio Arcimboldo, Giuseppe’s great-great-grandfather, was elected Archbishop of Milan in 1489, succeeding his deceased brother, Giovanni Arcimboldo. Between 1550 and 1555, Giovanni Angelo Arcimboldo, illegitimate son of Guido Antonio, reigned as Archbishop of Milan. He advised Giuseppe and steered him through the politics of the artists, humanists, and writers of the Milanese Court.

In Milan, Arcimboldo received training from his father in the arts, and also from artists of the Lombard School, such as Giuseppe Meda (active in Milan from 1551 to 1559) and Bernardino Campi (1522-1591), a distinguished painter from Cremona.

A certain artistic and scientific fascination for Leonardo da Vinci has been perceived in Arcimboldo‘s art. In fact, Giuseppe’s father, Biagio, had the good fortune to be friends with Bernardino Luini, a student of Leonardo da Vinci’s, who, after da Vinci’s death, inherited several of his master’s workbooks and sketches. Biagio Arcimboldo certainly studied these and, years later, taught da Vinci’s artistic and scientific style to his son Giuseppe.

Private collection, London

The Italian artists Biagio, Meda, and Campi were in contact with German artists, either working on commissions for the Milan Cathedral or creating tapestries for the Medici family. According to the Milan Cathedral archives, Arcimboldo was established as a master in 1549, working with his father in the painting and creation of sketches for the stained glass windows, organ doors, and canopy of the Cathedral’s altar. The most important stained glass windows, located within the apse, depict the Tales of the Life of Saint Catherine of Alexandria. The Christian legend deals with the martyrdom of Catherine, who refused to renounce her Christian faith for pagan gods. The decoration of these scenes was relatively elaborate, based on a combination of classic themes (amphorae, garlands, and cherubs) and Christian symbols (thrones, scallop shells, and ceremonial ornaments).

The architectural and ornamental concepts reflected the illusion of art and a mannerist taste. These forms also demonstrated Leonardo da Vinci’s influence on Arcimboldo, gained through the art of Milanese artist Gaudenzio Ferrari (1471-1546), who also worked on the Cathedral’s stained glass windows. A document from the archives of the Milan Cathedral, dated 1556, mentions that Arcimboldo‘s sketches for the Cathedral project were transposed onto glass by Corrado de Mochis, a master glazier from Cologne. During this period, Arcimboldo painted five emblematic insignias (today, lost) for Ferdinand, King of Bohemia, later Ferdinand I, Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation.

After the death of his father in 1551, Arcimboldo continued to work in Lombardy until 1558, after which time he undertook travels to Como and Monza. He created sketches of Old and New Testament themes for tapestries for the Como Cathedral. Flemish artists Johannes and Ludwig Karcher (active from 1517-1561), employed by the Gobelins Tapestry Manufactory, created a tapestry from these sketches.

Tapestry, 423 x 470 cm. Como Cathedral , Como

The names of the weavers appear on a scroll on the tapestry. Arcimboldo created eight scenes, sumptuously embellished with borders festooned with flowers, fruit, scrolls, and classical-style grotesques (grotteschi), such as can be seen in Death of the Virgin. In a private garden, in which the architecture echoes the styles of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, the Virgin rests in a casket surrounded by the mourning apostles, whilst the Santa Maria della Grazie Church can be seen in the background…

To get a better insight into the life and the work of Arcimboldo, continue this exciting adventure by clicking on: Arcimboldo , Fondation Louis Vuitton , Amazon UK , Amazon US , iTunes , Google , Amazon Australia , Amazon Canada , Barnes&Noble , Baker and Taylor , Amazon Italy , Amazon Japan , Amazon China , Amazon India , Amazon Mexico , Amazon Spain , Amazon France , numilog , youboox , Cyberlibris (French) , Cyberlibris (English) , Kobo , Scribd , Overdrive , Douban , Da

2017-12-15 02:25:10Rodin – Rilke – Hofmannsthal. Man and His Genius

Exhibition: Rodin – Rilke – Hofmannsthal. Man and His Genius

Date: Nov 17, 2017 − Mar 18, 2018

Venue: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

Musée Rodin, Paris.

“Writers work with words, sculptors with actions.“

— POMPONIUS GAURICUS: DE SCULPTURA (circa 1504)

“The hero is he who is immovably centered.”

— RALPH WALDO EMERSON

Rodin was solitary before he was famous. And fame, when it arrived, made him perhaps even more solitary. For in the end, fame is no more than the sum of all the misunderstandings that gather around a new name. There are many of these around Rodin, and clarifying them would be a long, arduous, and ultimately unnecessary task. They surround the name, but not the work, which far exceeds the resonance of the name, and which has become nameless, as a great plain is nameless, or a sea, which may bear a name in maps, in books, and among people, but which is in reality just vastness, movement, and depth.

The work of which we speak here has been growing for years. It grows every day like a forest, never losing an hour. Passing among its countless mani festations, we are overcome by the richness of discovery and invention, and we can’t help but marvel at the pair of hands from which this world has grown. We remember how small human hands are, how quickly they tire and how little time is given to them to create. We long to see these hands, which have lived the lives of hundreds of hands, of a nation of hands that rose before dawn to brave the long path of this work. We wonder whose hands these are. Who is this man?

His life is one of those that resists being made into a story. This life began and proceeded, passing deep into a venerable age; it almost seems to us as if this life had passed hundreds of years ago. We know nothing of it. There must have been some kind of childhood, a childhood in poverty; dark, searching, uncertain. And perhaps this childhood still belongs to this life. After all, as Saint Augustine once said, “where can it have gone? It may yet have all its past hours, the hours of anticipation and of desolation, the hours of despair and the long hours of need.”

This is a life that has lost nothing, that has forgotten nothing, a life that amasses even as it passes. Perhaps. In truth we know nothing of this life. We feel certain, however, that it must be so, for only a life like this could produce such richness and abundance.

Bronze, 61.5 x 22 x 46 cm. Musée Rodin , Paris.

Only a life in which everything is present and alive, in which nothing is lost to the past, can remain young and strong, and rise again and again to create great works. The time may come when this life will have a story, a narrative with burdens, epi sodes, and details. They will all be invented. Someone will tell of a child who often forgot to eat because it seemed more important to carve things in wood with a dull knife. They will find some encounter in the boy’s early days that seemed to promise future greatness, one of those retrospective prophecies that are so common and touching. It may well be the words a monk is said to have spoken to the young Michel Colombe almost five hundred years ago:

“Work, little one, look all you can, the steeple of Saint Pol, and the beautiful works ofthe Compagnons, look, love God and you will be grace of grand things.”

Musée Rodin, Paris.

And the grace of great things shall be given to you. Perhaps intuition spoke to the young man at one of the crossroads in his early days, and in infinitely more melodious tones than would have come from the mouth of a monk. For it was just this that he was after: the grace of great things. There was the Louvre with its many luminous objects of antiquity, evoking southerly skies and the near ness of the sea. And behind it rose heavy things of stone, traces of inconceiv able cultures enduring into epochs still to come. This stone was asleep, and one had the sense that it would awake at a kind of Last Judgment.

To get a better insight into the life and the work of Rodin, continue this exciting adventure by clicking on: Rodin , Amazon UK , Amazon US , iTunes , Google , Amazon Australia , Amazon Canada , Amazon Germany , Ceebo (Media Control), Ciando , Tolino Media , Open Publishing , Barnes&Noble , Baker and Taylor , Amazon Italy , Amazon Japan , Amazon China , Amazon India , Amazon Mexico , Amazon Spain , Amabook , Odilo , 24symbols , Arnoia , Nubico , Amazon France , numilog , youboox , Cyberlibris , Kobo , Scribd , Overdrive , Douban , Dangdang

2018-01-22 07:48:08Rubens: The Spiritual Father of Botero

Exhibition: Rubens. The Power of Transformation

Date: Feb 8 − May 28, 2018

Venue: Stadel Museum

Bacchus, 1638-1640. Oil on canvas, 191 x 161.3 cm. The State Hermitage Museum , St Petersburg.

The Life and Works of Peter Paul Rubens

The name of the great 17th century Flemish painter, Peter Paul Rubens is known throughout the world. The importance of his contribution to the development of European culture is generally recognised. The perception of life that he revealed in his pictures is so vivid, and fundamental human values are affirmed in them with such force, that we look upon Rubens’ paintings as a living aesthetic reality of our own time as well.

The museums of Russia have a superb collection of the great Flemish painter’s works. These are concentrated, for the most part, in The State Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg, which possesses one of the finest Rubens’ collections in the world. Three works, previously part of the Hermitage collection, now belong to The Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow. The Bacchanalia and The Apotheosis of the Infanta Isabella were bought for the Hermitage in 1779 together with the Walpole Collection (from Houghton Hall in England); The Last Supper came to the Hermitage in 1768 from the Cobenzl Collection (Brussels). These three paintings were then transferred to Moscow in 1924 and 1930.

One gains the impression that in the 17th century Rubens did not attract as much attention as later. This may appear strange: indeed his contemporaries praised him as the “Apelles of our day”. However, in the immediate years after the artist’s death, in 1640, the reputation which he had gained throughout Europe was overshadowed. The reasons for this can be found in the changing historical situation in Europe during the second half of the 17th century.

In the first decades of that century nations and absolutist states were rapidly forming. Rubens’ new approach to art could not fail to serve as a mirror for the most diverse social strata in many European countries who were keen to assert their national identity, and who had followed the same path of development. This aim was inspired by Rubens’ idea that the sensually perceived material world had value in itself; Rubens’ lofty conception of man and his place in the Universe, and his emphasis on the sublime tension between man’s physical and imaginative powers (born in conditions of the most bitter social conflicts), became a kind of banner of this struggle, and provided an ideal worth fighting for.

The National Gallery London

In the second half of the 17th century, the political situation in Europe was different. In Germany after the end of the Thirty Years’ War, in France following the Frondes, and in England as the result of the Restoration, the absolutist regime triumphed. There was an increasing disparity in society between conservative and progressive forces; and this led to a “reassessment of values” among the privileged, who were reactionary by inclination, and to the emergence of an ambiguous and contradictory attitude towards Rubens.

This attitude became as internationally prevalent as his high reputation during his lifetime, and this is why we lose trace of many of the artist’s works in the second half of the 17th century after they left the hands of their original owners (and why there is only rare mention of his paintings in descriptions of the collections of this period). Only in the 18th century did Rubens’ works again attract attention…

The Four Philosophers, 1611-1612. Oil on canvas, 164 x 139 cm.Galleria Palatina e Appartamenti Reali (Palazzo Pitti) , Polo Museale,

The Four Philosophers, 1611-1612. Oil on canvas, 164 x 139 cm.Galleria Palatina e Appartamenti Reali (Palazzo Pitti) , Polo Museale,

Florence.

Juno and Argus, c. 1610. Oil on canvas, 249 x 296 cm. Wallraf-Richartz-Museum & Fondation Corboud , Cologne.

To get a better insight into the life and the work of Rubens, continue this exciting adventure by clicking on: Rubens , Amazon UK , Amazon US , Ebook Gallery , iTunes , Google , Amazon Australia , Amazon Canada , Amazon Germany , Ceebo (Media Control), Ciando , Tolino Media , Open Publishing , Barnes&Noble , Baker and Taylor , Amazon Italy , Amazon Japan , Amazon China , Amazon India , Amazon Mexico , Amazon Spain , Amabook , Odilo , 24symbols , Arnoia , Nubico , Overdrive , Amazon France , numilog , youboox , Cyberlibris , Kobo , Scribd , Douban , Dangdang

2018-01-10 09:41:24Mucha: The Red Roses from Prague

Exhibition: Alphonse Mucha

Date: 12 October 2017 – 25 February 2018

Venue: Palacio de Gaviria, Madrid

Since the Art Nouveau revival of the 1960s, when students around the world adorned their rooms with reproductions of Mucha posters of girls with tendril-like hair and the designers of record sleeves produced Mucha imitations in hallucinogenic colours, Alphonse Mucha’s name has been irrevocably associated with the Art Nouveau style and with the Parisian fin-de-siècle. Artists rarely like to be categorised and Mucha would have resented the fact that he is almost exclusively remembered for a phase of his art that lasted barely ten years and that he was regarded as of lesser importance. As a passionate Czech patriot he would have also been unhappy to be regarded as a “Parisian” artist.

Spring (from the Seasons series), 1896. Coloured Lithograph, 14.5 x 28 cm.

Mucha Museum, Prague.

Mucha was born on July 14, 1860 at Ivancice in Moravia, then a province of the vast Habsburg Empire. It was an empire that was already splitting apart at the seams under the pressures of the burgeoning nationalism of its multi-ethnic component parts. In the year before Mucha’s birth, nationalist aspirations throughout the Habsburg Empire were encouraged by the defeat of the Austrian army in Lombardy that preceded the unification of Italy.

Mucha Museum, Prague.

In the first decade of Mucha’s life Czech nationalism found expression in the orchestral tone poems of Bedrich Smetana that he collectively entitled “Ma Vlast” (My country) and in his great epic opera “Dalibor” (1868). It was symptomatic of the Czech nationalist struggle against the German cultural domination of Central Europe that the text of “Dalibor” had to be written in German and translated into Czech. From his earliest days Mucha would have imbibed the heady and fervent atmosphere of Slav nationalism that pervades “Dalibor” and Smetana’s subsequent pageant of Czech history “Libuse” which was used to open the Czech National Theatre in 1881 and for which Mucha himself would later provide set and costume designs.

Salon des Cent : 20e Exposition, 1896. Coloured Lithograph, 43 x 63 cm.

Mucha Museum, Prague.

Mucha’s upbringing was in relatively humble circumstances, as the son of a court usher. His own son Jiri Mucha would later proudly trace the presence of the Mucha family in the town of Ivancice back to the fifteenth century. If his family was poor, Mucha’s upbringing was nevertheless not without artistic stimulation and encouragement. According to his son Jiri “He drew even before he learnt to walk and his mother would tie a pencil round his neck with a coloured ribbon so that he could draw as he crawled on the floor. Each time he lost the pencil, he would start howling.”

Prague.

His first important aesthetic experience would have been in the Baroque church of St. Peter in the local capital of Brno where from the age of ten he sang as a choir-boy in order to support his studies in the grammar school. During his four years as a chorister he came into frequent contact with the six years older Leoš Janácek, the greatest Czech composer of his generation with whom he shared a passion to create a characteristically Czech art…

To get a better insight into the life and the work of Mucha, continue this exciting adventure by clicking on: Mucha , Amazon UK , Amazon US , Ebook Gallery , iTunes , Google , Amazon Australia , Amazon Canada , Amazon Germany , Ceebo (Media Control), Ciando , Tolino Media , Open Publishing , Barnes&Noble , Baker and Taylor , Amazon Italy , Amazon Japan , Amazon China , Amazon India , Amazon Mexico , Amazon Spain , Amabook , Odilo , 24symbols , Arnoia , Nubico , Overdrive , Amazon France , numilog , youboox , Cyberlibris , Kobo , Scribd , Douban , Dangdang

2018-01-22 07:59:01Gallé: Time’s Fragility

Exhibition: A Passionate Eye for Japanese Art. Japonisme in Emile Gallé’s Work

Date: 3 April 2017 – 31 March 2018

Venue: Kitazawa Museum of Art

During the end of the 19th century, Western Europe experienced a great rebirth and reinvigoration in decorative arts, with a focus on the imitation of nature. In fact, in the 1860s, vital scientific works (by Haeckel, Kommode, Blossfeldt, etc.) were published, offering the new art a repertoire of forms, and directing it towards a path of modernity. At the same time, a taste for Japanese art started to develop, seen through personalities such as Hayashi Tadamasa, an art dealer, who set up residence in France, enabling Western Europe to discover Japanese modes of production. Japanese art is based on the observation of nature, on the poetic interpretation of natural forms. Science and art displayed a similar move towards renewal during the 19th century.

This went hand in hand with an artistic awakening of nationalities throughout Western Europe. It was no longer a question of the past nor foreign taste. Instead each nation developed its own aesthetic. Above all, functionality became a priority in arts, decorative embellishments were reduced and useful decoration and objects moved to the foreground. Such art was forbidden during the century through various trends: “[this century] had no folk art“ said Émile Gallé in 1900.

Stuttgart.

In the 1870s to the 1880s, their forces returned. What was seen as superfluous in the past, was revived in the field of arts. All these events occurred in Western Europe at the same time, and led in the late 19th century to the birth of Art Nouveau, a name that perfectly reflected the innovativeness of the art movement. Although an overall stylistic similarity existed, the formal development of Art Nouveau varied from land to land.

The 1889 World Exposition in Paris reflected the scale of the influence of Art Nouveau, exposing a complete image not only of the various areas of production, but also of the national tendencies. Art Nouveau exploded in France in 1895 in a similar way that Alphonse Mucha’s placard for Sarah Bernhardt in the role of Gismonda caused a sensational uproar. In December of the same year, Siegfried Bing, an art dealer with German ancestry but French nationality, opened a gallery entirely devoted to Art Nouveau and played a significant role in the diffusion of the movement.

case, date unknown. Faience. Landesmuseum Württemberg ,

Stuttgart.

In the realm of decorative arts Émile Gallé (1846-1904) – a Nancy-born glassmaker, carpenter, and ceramicist – acquired over the decade much fame with his Art-Nouveaustyle art pieces. He incorporated his passion for botany in his father‘s trade of pottery and glassware in 1877. His inspiration came from nature and from the works of Japanese artists, which he collected. He developed new techniques, filed patents, and directed various steps in the process of development, a legacy in the industrial revolution in his workshops. During the 1889 World Exposition, Gallé received three awards for his entries. He then acquired the epithet homo triplex from the critic Roger Marx.

glaze, height: 16 cm, width: 27 cm, depth: 18 cm. Musées royaux

d’Art et d’Histoire , Brussels.

In 1901, together with Victor Prouvé (1858-1943), Louis Majorelle (1859-1926), and Eugène Vallin (1856-1922), he founded Alliance Provinciale des Industries d’Art, also known as École de Nancy. Their goal was to eliminate the separation between disciplines: there should no longer exist a distinction between experienced and unexperienced artists. Nature is the foundation of their aesthetic, seen through the creation of flower and plant stylisation. After Art Nouveau reached its peak in 1900, he quickly disappeared from the world of art. In contradiction to his major speeches, Art Nouveau is a luxury style, difficult to reproduce on a large scale. The First International Exhibition of Modern Decorative Arts in Turin of 1902 indicated that a new art movement was already underway: Art Deco.

To get a better insight into the life and the work of Gallé, continue this exciting adventure by clicking on: Gallé , Amazon UK , Amazon US , Ebook Gallery , iTunes , Google , Amazon Australia , Amazon Canada , Amazon Germany , Ceebo (Media Control), Ciando , Tolino Media , Open Publishing , Barnes&Noble , Baker and Taylor , Amazon Italy , Amazon Japan , Amazon China , Amazon India , Amazon Mexico , Amazon Spain , Amabook , Odilo , 24symbols , Arnoia , Nubico , Overdrive , Amazon France , numilog , youboox , Cyberlibris , Kobo , Scribd , Douban , Dangdang

2018-02-01 06:28:16Degas: Light as a Tutu of a Ballet Student of the Paris Opers

Exhibition: The Art of Pastel From Degas to Redon

Date: 15 September 2017 – 8 April 2018

Venue: Le Petit Palais

New York

Edgar Degas was closest to Pierre-Auguste Renoir in the Impressionist’s circle, for both favoured the animated Parisian life of their day as a motif in their paintings. Degas did not attend Charles Gleyre’s studio; most likely he first met the future Impressionists at the Café Guerbois. It is not known exactly where he met Édouard Manet. Perhaps they were introduced to one another by a mutual friend, the engraver Félix Bracquemond, or perhaps Manet, struck by Degas’ audacity, first spoke to him at the Louvre in 1862. Two months after meeting the Impressionists, Degas exhibited his canvases with Claude Monet’s group, and became one of the most loyal of the Impressionists: not only did he contribute works to each of their exhibitions except the seventh, he also participated very actively in organising them. All of which is curious, because he was rather distinct from the other Impressionists.

Musée d’Orsay , Paris.

Degas came from a completely different milieu than that of Monet, Renoir, and Alfred Sisley. His grandfather René-Hilaire de Gas, a grain merchant, had been forced to flee from France to Italy in 1793 during the French Revolution. Business prospered for him there. After establishing a bank in Naples, de Gas wed a young girl from a rich Genoan family. Edgar preferred to write his name simply as Degas, although he happily maintained relations with his numerous de Gas relatives in Italy.

Enviably stable by nature, Degas spent his entire life in the neighbourhood where he was born. He scorned and disliked the Left Bank, perhaps because that was where his mother had died. In 1850, Edgar Degas completed his studies at Lycée Louis-le-Grand, and, in 1852, received his degree in law. Because his family was rich, his life as a painter unfolded far more smoothly than for the other Impressionists.

The Philadelphia Museum of Fine Arts , Philadelphia.

Degas started his apprenticeship in 1853 at the studio of Louis-Ernest Barrias and, beginning in 1854, studied under Louis Lamothe, who revered Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres above all others and transmitted his adoration for this master to Edgar Degas. Degas’ father was not opposed to his son’s choice. On the contrary: when, after the death of his wife, he moved to Rue Mondovi, he set up a studio for Edgar on the fourth floor, from which the Place de la Concorde could be seen over the rooftops. Edgar’s father himself was an amateaur painter and connoisseur; he introduced his son to his many friends. Among them were Achille Deveria, curator of the Department of Prints and Drawings at the Bibliothèque Nationale, who permitted Edgar to copy from the drawings of the Old Masters: Rembrandt, Dürer, Goya, Holbein.

His father also introduced him to his friends in the Valpinçon family of art collectors, at whose home the future painter met the great Ingres. All his life Degas would remember Ingres’ advice as one would remember a prayer: “Draw lines … Lots of lines, whether from memory or from life” (Paul Valéry, Écrits sur l’Art [Writings on Art], Paris, 1962). Starting in 1854, Degas travelled frequently to Italy: first to Naples, where he made the acquaintance of his numerous cousins, and then to Rome and Florence where he copied tirelessly from the Old Masters. His drawings and sketches already revealed very clear preferences: Raphael, Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Andrea Mantegna, but also Benozzo Gozzoli, Ghirlandaio, Titian, Fra Angelico, Uccello, and Botticelli. He went to Orvieto Cathedral specifically to copy from the frescoes of Luca Signorelli, and visited Perugia and Assisi. The pyrotechnics of Italian painting dazzled him. Degas was lucky like no other.

One can only marvel at the sensitivity Edgar’s father demonstrated with respect to his son’s vocation, at his insight into his son’s goals, and at the way he was able to encourage the young painter. “You’ve taken a giant step forwards in your art, your drawing is strong, your colour tone is precise,” he wrote his son. “You no longer have anything to worry about, my dear Edgar, you are progressing beautifully. Calm your mind and, with tranquil and sustained effort, stick to the furrow that lies before you without straying. It’s your own – it is no one else’s. Go on working calmly, and keep to this path” (J. Bouret, Degas, Paris, 1987).

To get a better insight into the life and the work of Degas, continue this exciting adventure by clicking on: Degas, Amazon UK , Amazon US , Ebook Gallery , iTunes , Google , Amazon Australia , Amazon Canada , Amazon Germany , Ceebo (Media Control), Ciando , Tolino Media , Open Publishing , Thalia , Weltbild , eBook.de , Hugendubel.de , Barnes&Noble , Baker and Taylor , Amazon Italy , Amazon Japan , Amazon China , Amazon India , Amazon Mexico , Amazon Spain , Amabook , Odilo , Casa del libro , 24symbols , Arnoia , Nubico , Overdrive , Amazon France , numilog , youboox , Cyberlibris , Kobo , Scribd , Douban , Dangdang

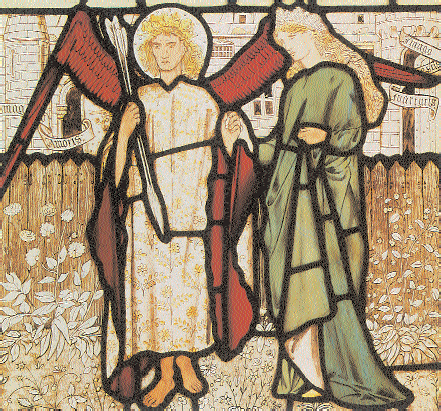

2018-02-07 04:23:29Pre-Raphaelites: The Revolutionary Brotherhood: Return to the Middle Age

Exhibition: Reflections: Van Eyck and the Pre-Raphaelites

Date: Until April 2, 2018

Venue: National Gallery London

Oil on canvas, 372 x 296 cm. Art Gallery of New South Wales , Sydney

English Art in 1844

Until 1848, one could admire art in England, but would not be surprised by it. Reynolds and Gainsborough were great masters, but they were 18th-century painters rather than 18th-century English painters. It was their models, their ladies and young girls, rather than their brushwork, which gave an English character to their creations. Their aesthetic was similar to that of the rest of Europe at that time. Walking through the halls of London museums, one could see different paintings, but no difference in manner of the painting and drawing, or even in the conception or composition of a subject.

The Eve of St Agnes. William Holman Hunt , 1848. Oil on canvas, 77.4 x 113 cm

Guildhall Art Gallery , Corporation of London, London

Only the landscape painters, led by Turner and Constable, sounded a new and powerful note at the beginning of the century. But one of them remained the only individual of his species, imitated as infrequently in his own country as elsewhere, while the work of the other was so rapidly imitated and developed by the French that he had the glory of creating a new movement in Europe rather than the good chance of providing his native country with a national art.

As for the others, they painted, with more or less skill, in the same way as artists of other nationalities. Their dogs, horses, village politicians, which formed little kitchen, interior, and genre scenes were only interesting for a minute, and even then the artists did not handle them as well as the Dutch. Weak, muddy colours layered over bitumen, false and lacking in vitality, with shadows too dark and highlights too intense. Soft, hesitating outlines that were vague and generalising. And as the date of 1850 approached, Constable’s words of 1821 resonated, “In thirty years English art will have ceased to exist.”

Oil on canvas, 83.2 x 65.4 cm. Tate Britain , London

And yet, if we look closely, two characteristics were there, lying dormant. First, the intellectuality of the subject. The English had always chosen scenes that were interesting, even a bit complicated, where the mind had as much to experience as the eye, where curiosity was stimulated, the memory put into play, and laughter or tears provoked by a silent story. It was rapidly becoming an established idea (visible in Hogarth) that the paintbrush was made for writing, storytelling, and teaching, not simply for showing.

However, prior to 1850 it merely spoke of the pettiness of daily life; it expressed faults, errors or rigid conventional feelings; it sought to portray a code of good behaviour. It played the same role as the books of images that were given to children to show them the outcomes of laziness, lying, and greed. The other quality was intensity of expression. Anyone who has seen Landseer’s dogs, or even a few of those animal studies in Englishillustrated newspapers where the habitus corporis is followed so closely, the expression so wellstudied, can easily understand what is meant by “intensity of expression”.

Oil on canvas, 120 x 182 cm. Johannesburg Art Gallery , Johannesburg

But in the same way that intellectuality was only present before 1850 in subjects that were not worth the effort, intensity of expression was only persistently sought and successfully attained in the representation of animal figures. Most human figures had a banal attitude, showing neither expressiveness nor accuracy, nor picturesque precision, and were placed on backgrounds imagined in the studio. They were prepared using academic formulas, according to general principles that were excellent in themselves, but poorly understood and lazily applied.

Such was English art until Ford Madox Brown came back from Antwerp and Paris, bringing an aesthetic revolution along with him. That is not to say that all the trends that have emerged and all the individuality that has developed since that time originated from this one artist, or that at the moment of his arrival, none of his compatriots were feeling or dreaming the same things that he was. But one must consider that in 1844, when William the Conqueror was exhibited for the first time, no trace of these new things had yet appeared. Rossetti was sixteen years old, Hunt seventeen, Millais fifteen, Watts twenty-six, Leighton fourteen, and Burne-Jones eleven, and consequently not one of these future masters had finished his training.

Christ in the House of his Parents (“The Carpenter’s Shop”). John Everett Millais , 1849-1850. Oil on canvas, 86.4 x 139.7 cm. Tate Britain , London

If one considers that the style of composition, outline, and painting ushered in by Madox Brown can be found fifty years after his first works in the paintings of Burne-Jones, having also appeared in those of Burne-Jones’ master Rossetti, one must acknowledge that the exhibitor of 1844 played the decisive role of sower, whereas others only tilled the soil in preparation or harvested once the crop had arrived.

To get a better insight into the life and the work of the Pre-Raphaelites, continue this exciting adventure by clicking on: Pre-Raphaelites, Amazon UK , Amazon US , Ebook Gallery , iTunes , Google , Amazon Australia , Amazon Canada , Renaud-Bray , Archambault , Les Libraires , Amazon Germany , Ceebo (Media Control), Ciando , Tolino Media , Open Publishing , Thalia , Weltbild , eBook.de , Hugendubel.de , Barnes&Noble , Baker and Taylor , Amazon Italy , Amazon Japan , Amazon China , Amazon India , Amazon Mexico , Amazon Spain , Amabook , Odilo , Casa del libro , 24symbols , Arnoia , Nubico , Overdrive , Amazon France , numilog , youboox , Decitre , Chapitre , Fnac France , Fnac Switzerland , ibrairiecharlemagne.com , Bookeen , Cyberlibris , Kobo , Scribd , Douban , Dangdang

2018-02-27 04:36:50Toulouse-Lautrec and the French can-can

Exhibition: Toulouse-Lautrec and the Pleasures of the Belle Époque

Date: February, 8 – May, 6 , 2018

Venue: Canal de Isabel II Foundation , Madrid.

Plakatsammlung, Museum für Gestaltung Zürich , Zurich

Frustrated and unsuccessful, an artist laments in an illustration in the German satirical magazine Simplicissimus issued in 1910: “You know, if one were a Frenchman, or dead, or a pervert – best of all, a dead French pervert – it might be possible to enjoy life!”. He is endeavouring to paint while his domestic life crowds in on him from every direction:children run about screaming, toys lie scattered on the floor, and his wife is hanging up washing on a line stretched across his studio.

The idea that genius and domesticity are incompatible with one another was hardly new, but the artist’s comment shows how quickly the turbulent lives and premature deaths of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Paul Gauguin had entered popular mythology. Lautrec, who died aged thirty-seven in 1901, Gauguin, who died aged fifty-five in 1903, and the Dutch-born but French-by-adoption Vincent van Gogh did more than any others to colour popular ideas about the ‘artist’ in the twentieth century.

at Malromé Castle), 1881-1883. Oil on canvas, 93.5 x 81 cm. Musée Toulouse-Lautrec , Albi

Although the notion of the artist as a self-destructive outsider reached its peak at the end of the nineteenth century with Lautrec, Gauguin and van Gogh, its origin can be traced back to the late eighteenth century when political, cultural and economic revolutions transformed the way artists saw themselves and their relations with the world around them. In 1765, under the ancien régime, the pastel artist Maurice Quentin de La Tour depicted himself as an aspiring courtier, with powdered wig, velvet jacket and an ingratiating smile.

Still Life, Pool Table, 1882. Oil on canvas, 27 x 22 cm. Musée Toulouse-Lautrec , Albi

Somewhat less pretentiously and dressed a good deal more practically, his contemporary Jean-Baptiste Siméon Chardin also showed himself as a well-adjusted and contented member of society on a lower social rung. Two or three decades later, the smiles and benign expressions no longer appear on the faces of a new generation of young artists including Jacques-Louis David, Henry Fuseli and Joseph Turner. These are young men in complex and even tormented states of mind, whose self-portraits challenge the viewer with their ferocious stares.

A link between the angry young men of Romanticism and the peintres maudits of the late nineteenth century is provided by Gustave Courbet who, in the 1840s and 50s, developed the myth of the artist in a series of self-portraits culminating famous Bonjour M. Courbet.

In this painting, Courbet flouts social conventions with his bohemian appearance and his lordly body language as he greets his wealthy bourgeois patron. Lautrec, too, relished in the role of bohemian outsider, and celebrated it in a series of elaboratelyposed group photographs of himself and his friends in outrageous fancy-dress costumes. Most hilariously, in 1884 he painted a parody of Pierre Puvis de Chavannes’ noble masterpiece The Sacred Grove Cherished by the Arts and Muses in which he shows himself and his drunken friends bursting precipitately into the sacred grove. He emphasises his own grotesque and dwarflike appearance. Seen from behind, he seems to be urinating in front of Puvis’ solemn ladies.

To get a better insight into the life and the work of the Toulouse-Lautrec, continue this exciting adventure by clicking on: Toulouse-Lautrec, Amazon UK , Amazon US , Ebook Gallery , iTunes , Google , Amazon Australia , Amazon Canada , Renaud-Bray , Archambault , Les Libraires , Amazon Germany , Ceebo (Media Control), Ciando , Tolino Media , Open Publishing , Thalia , Weltbild , eBook.de , Hugendubel.de , Barnes&Noble , Baker and Taylor , Amazon Italy , Amazon Japan , Amazon China , Amazon India , Amazon Mexico , Amazon Spain , Amabook , Odilo , Casa del libro , 24symbols , Arnoia , Nubico , Overdrive , Amazon France , numilog , youboox , Decitre , Chapitre , Fnac France , Fnac Switzerland , ibrairiecharlemagne.com , Bookeen , Cyberlibris , Kobo , Scribd , Douban , Dangdang

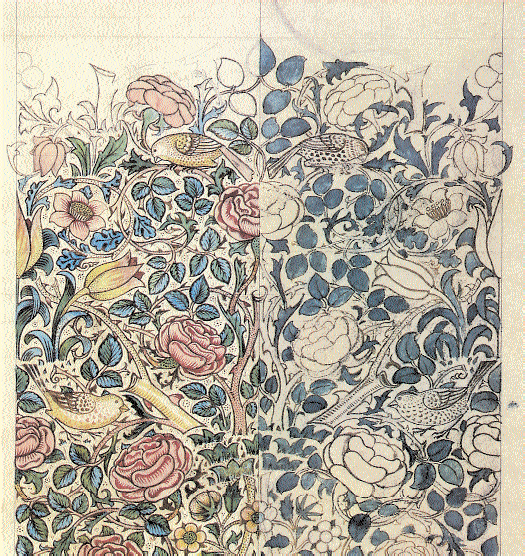

2018-02-28 08:39:04William Morris: A Pattern is either right or wrong…It is no stronger than its weakest point

Exhibition: William Morris and the Arts & Crafts movement in Great Britain

Date: February 22 – May 20, 2018

Venue: Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya | Barcelona Spain

From the middle of the nineteenth century to the beginning of the twentieth century, we have passed through a period of aesthetic discontent which continues and which is distinct from the many kinds of discontent by which men have been troubled in former ages. No doubt aesthetic discontent has existed before; men have often complained that the art of their own time was inferior to the art of the past; but they have never before been so conscious of this inferiority or felt that it was a reproach to their civilisation and a symptom of some disease affecting the whole of their society.

William Morris and William Frend De Morgan (for the design) and Architectural Pottery Co. (for the production), Panel of tiles, 1876. Slip-covered tiles, hand-painted in various colours, glazed on earthenware blanks, 160 x 91.5 cm. Victoria & Albert Museum, London.

We, powerful in many things beyond any past generation of men, feel that in this one respect we are more impotent than many tribes of savages. We can make things such as men have never made before; but we cannot express any feelings of our own in the making of them, and the vast new world of cities which we have made and are making so rapidly, seems to us, compared with the little slow-built cities of the past, either blankly inexpressive or pompously expressive of something which we would rather not have expressed. That is what we mean when we complain of the ugliness of most modern things made by men. They say nothing to us or they say what we do not want to hear, and therefore we should prefer a world without them.

For us there is a violent contrast between the beauty of nature and the ugliness of man’s work which most past ages have felt little or not at all. We think of a town as spoiling the country, and even of a single modern house as a blot on the face of the earth. But in the past, until the eighteenth century, men thought that their own handiwork heightened the beauty of nature or was, at least, in perfect harmony with it. We are aware of this harmony in a village church or an old manor house or a thatched cottage, however plain these may be; and wonder at it as a secret that we have lost.

Indeed, it is a secret definitely lost in a period of about forty years, between 1790 and 1830. In the middle of the eighteenth century, foolish furniture, not meant for use, was made for the rich, both in France and in England; furniture meant to be used was simple, well made, and well proportioned. Palaces might have been pompous and irrational, but plain houses still possessed the merits of plain furniture. Indeed, whatever men made, without trying to be artistic, they made well; and their work had a quiet unconscious beauty, which passed unnoticed until the secret of it was lost.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (for the design) and Morris & Co. (for the production), The Rossetti Armchair, 1870-1890. Ebonized beech, with red painted decoration and rush seat, 88.8 x 49.5 x 53 cm. Victoria & Albert Museum , London.

When the catastrophe came, it affected less those arts such as painting, which are supported by the conscious patronage of the rich, than those more universal and necessary arts which are maintained by a general and unconscious liking for good workmanship and rational design. There were still painters like Turner and Constable, but soon neither rich nor poor could buy new furniture or any kind of domestic implement that was not hideous. Every new building was vulgar or mean, or both. Everywhere the ugliness of irrelevant ornament was combined with the meanness of grudged material and bad workmanship.

At the time no one seems to have noticed this change. None of the great poets of the Romantic Movement, except perhaps Blake, gives a hint of it. They turned with an unconscious disgust from the works of man to nature; and if they speak of art at all it is the art of the Middle Ages, which they enjoyed because it belonged to the past. Indeed the Romantic Movement, so far as it affected the arts at all, only afflicted them with a new disease. The Gothic revival, which was a part of the Romantic movement, expressed nothing but a vague dislike of the present with all its associations and a vague desire to conjure up the associations of the past as they were conjured up in Romantic poetry. Pinnacles, pointed arches and stained glass windows were symbols, like that blessed word Mesopotamia; and they were used without propriety or understanding. In fact, the revival meant nothing except that the public was sick of the native ugliness of its own time and wished to make an excursion into the past, as if for change of air and scene.

To get a better insight into the life and the work of the William Morris, continue this exciting adventure by clicking on: William Morris, Amazon UK , Amazon US , Ebook Gallery , iTunes , Google , Amazon Australia , Amazon Canada , Renaud-Bray , Archambault , Les Libraires , Amazon Germany , Ceebo (Media Control), Ciando , Tolino Media , Open Publishing , Thalia , Weltbild , eBook.de , Hugendubel.de , Barnes&Noble , Baker and Taylor , Amazon Italy , Amazon Japan , Amazon China , Amazon India , Amazon Mexico , Amazon Spain , Amabook , Odilo , Casa del libro , 24symbols , Arnoia , Nubico , Overdrive , Amazon France , numilog , youboox , Decitre , Chapitre , Fnac France , Fnac Switzerland , ibrairiecharlemagne.com , Bookeen , Cyberlibris , Kobo , Scribd , Douban , Dangdang

2018-03-12 06:53:27Mantegna and the Concept of Total Illusion

Exhibition: Mantegna and Bellini

Date: March 21 – July 1, 2018

Venue: Fondazione Querini Stampalia | Venice, Italy

Room of the bride and groom,1470

The art of Andrea Mantegna (born c.1431, died 1506) has long maintained a broad and deep appeal. From the impressive illusionism of his earliest works to the narrative power of his mature paintings, Mantegna’s art remained vivid and heroic, dramatic and emotional. They are also painted in stunning detail: pebbles, blades of grass, veins, and hair are rendered with excruciating care, and he depicted even in his great narrative works the mundane particulars of earthly existence, showing laundry hanging out to dry and buildings fallen into disrepair. He had a deep interest in human nature and issues of moral character.

The Holy Family with St Elizabeth and the young St John, c. 1485-1488.

Tempera and gold on canvas, 62.9 x 51.3 cm. Kimbell Art Museum , Fort Worth.

Perhaps most strikingly, Mantegna’s pictures are filled with references to classical antiquity. No other painter of the fifteenth century so thoroughly understood and abundantly included in his art the costumes, drapery folds, inscriptions, architecture, subject matter, ethical attitude, and other aspects of ancient classical civilisation. And instead of the cool classicism of later centuries, his vision of Greco-Roman civilisation is lively and has a familiar and nostalgic air about it.

For him, antiquity was a near, palpable presence, one which he sought constantly to bring to colourful existence in his pictures. It is this thirst for a vanished classical past that places Mantegna most firmly in the context of his time, as his art was favoured most warmly by Renaissance contemporaries who shared his visionary quest to revive the moral strength and naturalism which marked the art of antiquity.

The Descent into Limbo, c. 1490. Tempera on panel, 38.2 x 42.3 cm.

Private collection.

Mantegna was a leader in the renewal of culture occurring during his time, a movement we call the Renaissance, or “rebirth.” In the fifteenth century, classical civilisation was a whole universe open to rediscovery. It offered an alternative to the confining, medieval world of scholastic thought and Christian theology. Classicism meant the liberation of the mind and the joys of literary study. The writers and artists of antiquity indulged freely in the delights of the material world, an attitude shared by Mantegna and many of his contemporaries.

Sandro Botticelli, St Augustine in his Cell, 1494. Tempera on panel, 41 x 27 cm.

Galleria degli Uffizi , Florence.

Renaissance men found spiritual ancestors from centuries past who had similar ideas about virtue and vice, and whose secular sensibility embraced a naturalistic art that was idealised in its formal perfection and its harmonious proportions. Mantegna painted his classical visions for enthusiasts, men and women who were dilettantes in the original sense of the word, delighting in their new discoveries. His life and works contributed to the air of celebration and self-congratulation characterising much of Renaissance culture.

Masolino, Healing of the Cripple and Raising of Tabatha, 1426-1427.

Fresco, 255 x 588 cm (full fresco). Brancacci Chapel, Santa Maria del

Carmine, Florence.

Some modern scholars avoid using the word “Renaissance” and, rather than see the period as being an age of confidence and a glorious rebirth of values, they describe Italian culture from 1400 to 1600 as one of conflicting interests, a hesitant and contradictory world in which the men and women cautiously “negotiated” their places in society. Period texts, however, reveal a mentality not as tentative and fearful as modern scholarship would have us believe.

Martyrdom of St Christopher, c. 1448-1457. Fresco. Ovetari Chapel,

Church of the Eremitani, Padua.

To be sure, the Renaissance had its political crises and social dislocations. It is important to bear in mind the larger picture: leading patrons, intellectuals, and artists in Italy felt they were living in a period of rebirth, and were forcibly helping to shape a new order of things. In the visual sphere, Renaissance writers about art – Lorenzo Ghiberti, Leon Battista Alberti, and Giorgio Vasari, for example – were quite clear in seeing the Middle Ages as a dark period, and their own age as one of enlightenment and human improvement. They looked back with admiration towards the achievement of the Greeks and Romans, and called for, not a bland imitation of antiquity, but an embracing of the ideals and values which made ancient societies superior to the cultural decline that followed: reason, an acceptance of natural law, and ethical moderation.

To get a better insight into the life and the work of Mantegna, continue this exciting adventure by clicking on: Mantegna, Amazon UK , Amazon US , Ebook Gallery , iTunes , Google , Amazon Australia , Amazon Canada , Renaud-Bray , Archambault , Les Libraires , Amazon Germany , Ceebo (Media Control), Ciando , Tolino Media , Open Publishing , Thalia , Weltbild , eBook.de , Hugendubel.de , Barnes&Noble , Baker and Taylor , Amazon Italy , Amazon Japan , Amazon China , Amazon India , Amazon Mexico , Amazon Spain , Amabook , Odilo , Casa del libro , 24symbols , Arnoia , Nubico , Overdrive , Amazon France , numilog , youboox , Decitre , Chapitre , Fnac France , Fnac Switzerland , ibrairiecharlemagne.com , Bookeen , Cyberlibris , Kobo , Scribd , Douban , Dangdang

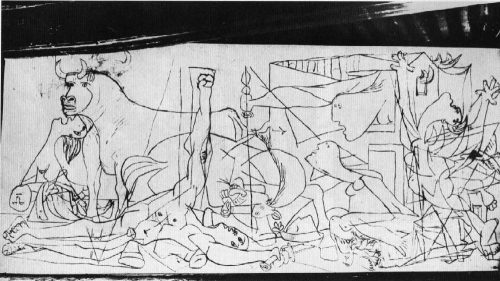

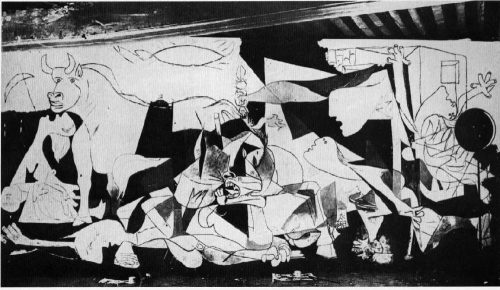

2018-03-26 07:08:20When German soldiers used to come to my studio and look at my pictures of Guernica, they'd ask 'Did you do this?'. And I'd say, 'No, you did.'

Exhibition: Guernica

Date: March 27 – July 29, 2018

Venue: Musée national Picasso | Paris, France

When German soldiers used to come to my studio and look at my pictures of Guernica, they'd ask 'Did you do this?'. And I'd say, 'No, you did.' – Pablo Picaaso

GUERNICA, 1937. Oil on canvas, 349.3 x 776.6 cm

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid

The bloody historical event that moved Picasso to create this masterpiece in one month took place shortly before its first exhibition at the 1937 World Exposition in Paris, where it was shown after it was commissioned by the government of the Spanish Republic. The images and feelings of the three-hour bombing and destruction of the Basque town of Guernica by Nazi planes were still fresh in the public consciousness. The brutally stark, monochrome work was controversial both as a reactive political statement and as art. The black and white must have been inspired by photographs taken of the war, such as those of Robert Capa. Despite the symbolism given to the different elements since the very creation of the painting, Picasso remained very secretive on the meanings of Guernica’s hidden themes and images.

Guernica state 1, 1937. Photograph by Dora Maar

Guernica state 3, 1937. Photograph by Dora Maar

Rarely do we get the chance to see a masterpiece in the making. Dora Maar, Picasso’s lover at the time, documented the frantic activity of Picasso during the month he spent working on what was to become Guernica. The photographs of these two states demonstrate that Picasso invented some of the painting as he went along. Note, in state 1, how a clenched fist takes up the space that would later be occupied by the head of the horse. Even when Picasso began applying paint to the canvas, we see elements that would be modified in the finished version.

Bull's head. Study for 'Guernica', 1937. Graphite and gouache on tracing cloth, 23 x 29 cm. Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid

One of the most recognisable figures in Guernica – and in Picasso’s whole oeuvre – is the bull. Many writers understand this to be a symbol of Spain, although Picasso is als noted to have said that in Guernica, it assumed the role of the brutality of fascism.

Mother and Dead Child (IV), 1937. Graphite, gouache, collage, and colour stick on tracing cloth, 23.1 x 29.2 cm. Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía , Madrid

Although one of Guernica’s most distinctive and powerful elements is its reduced chromatic scale, Picasso achieves great dramatism in many of his coloured studies. Such is the case with this Mother and Dead Child, where Picasso even added real hair to the figure of the woman. The tight composition and the nervous, hard lines define its dramatic immediacy.

Head of a Weeping Woman (Study for 'Guernica'), 1937.

Graphite, gouache, and colour stick on tracing cloth, 23.2 x 29.3 cm

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía , Madrid

Of all the iconic images that make up Guernica, perhaps the most dramatic is the woman who screams in distress whilst holding her dead child in her arms. Picasso made many drawings and paintings depicting weeping women such as these. Although the present study of this screaming head is not like the one on the final painting, it gives us an insight into the many different possibilities that Picasso considered before making the final work. It also speaks of the artist’s original intentions of including colour in the painting.

To get a better insight into the life and the work of Picasso, continue this exciting adventure by clicking on: Picasso, Amazon UK , Amazon US , Ebook Gallery , iTunes , Google , Amazon Australia , Amazon Canada , Renaud-Bray , Archambault , Les Libraires , Amazon Germany , Ceebo (Media Control), Ciando , Tolino Media , Open Publishing , Thalia , Weltbild , Barnes&Noble , Baker and Taylor , Amazon Italy , Amazon Japan , Amazon China , Amazon India , Amazon Mexico , Amazon Spain , Amabook , Odilo , Casa del libro , 24symbols , Arnoia , Nubico , Overdrive , Amazon France , numilog , youboox , Decitre , Chapitre , Fnac France , Fnac Switzerland , ibrairiecharlemagne.com , Bookeen , Cyberlibris , Kobo , Scribd , Douban , Dangdang

2018-04-02 07:34:06Everything you can imagine is real

Exhibition: Guernica

Date: 27 March - 29 July 2018

Venue: Canal de Isabel II Foundation, Madrid. Musée national Picasso | Paris, France

BREAD AND FRUIT DISH ON A TABLE, 1908-1909 Oil on canvas, 163.7 x 132.1 cm Kunstmuseum Basel, Basel

Although, as Picasso himself put it, he “led the life of a painter” from very early childhood, and although he expressed himself through the plastic arts for eighty uninterrupted years, the essence of Picasso’s creative genius differs from that usually associated with the notion of the artiste-peintre. It might be more correct to consider him an ‘artist-poet’ because his lyricism, his psyche, unfettered by mundane reality, and his gift for the metaphoric transformation of reality are no less inherent in his visual art than they are in the mental imagery of a poet.

The Old Jew, 1903 Oil on canvas, 125 x 92 cm. Pushkin Museum, Moscow

According to Pierre Daix, “Picasso always considered himself a poet who was more prone to express himself through drawings, paintings, and sculptures.”1 Always? That calls for clarification. It certainly applies to the 1930s, when he wrote poetry, and to the 1940s and 1950s, when he turned to writing plays. There is, however, no doubt that from the outset Picasso was always “a painter among poets, a poet among painters”.

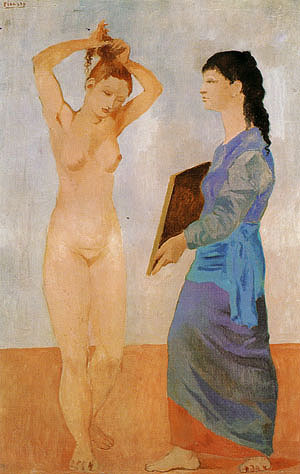

La Coiffure, 1906 Oil on canvas, 174.9 x 99.7 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Picasso had a craving for poetry and attracted poets like a magnet. When they first met, Guillaume Apollinaire was struck by the young Spaniard’s unerring ability “to straddle the lexical barrier” and grasp the fine points of recited poetry. One may say without fear of exaggeration that whilst Picasso’s close friendship with the poets Jacob, Apollinaire, Salmon, Cocteau, Reverdy, and Éluard left an imprint on each of the major periods of his work, it is no less true that his own innovative work had a strong influence on French (and not only French) 20th-century poetry.

LES DEMOISELLES DÊAVIGNON, 1907 Oil on canvas, 243.9 x 233.7 cm The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Picasso, however, was born a Spaniard and, so they say, began to draw before he could speak. As an infant he was instinctively attracted to the artist’s tools. In early childhood he could spend hours in happy concentration drawing spirals with a sense and meaning known only to himself; or, shunning children’s games, he would trace his first pictures in the sand. This early self-expression held out promise of a rare gift.

TWO WOMEN RUNNING ON THE BEACH, 1922

Gouache on plywood, 32.5 x 41.1 cm Musée Picasso Paris, Paris

The first phase of life, preverbal, preconscious, knows neither dates nor facts. It is a dream-like state dominated by the body’s rhythms and external sensations. The rhythms of the heart and lungs, the caresses of warm hands, the rocking of the cradle, the intonation of voices, that is what it consists of. Now the memory awakens, and two black eyes follow the movements of things in space, master desired objects, express emotions.

To get a better insight into the life and the work of the Picasso, continue this exciting adventure by clicking on: Pablo Picasso, Amazon UK , Amazon US , Ebook Gallery , iTunes , Google , Amazon Australia , Amazon Canada , Renaud-Bray , Archambault , Les Libraires , Amazon Germany , Ceebo (Media Control), Ciando , Tolino Media , Open Publishing , Thalia , Weltbild , Barnes&Noble , Baker and Taylor , Amazon Italy , Amazon Japan , Amazon China , Amazon India , Amazon Mexico , Amazon Spain , Amabook , Odilo , Casa del libro , 24symbols , Arnoia , Overdrive , Amazon France , numilog , youboox , Decitre , Chapitre , Fnac France , Fnac Switzerland, ibrairiecharlemagne.com , Bookeen , Cyberlibris , Kobo , Scribd , Douban , Dangdang.

2018-04-03 08:43:33